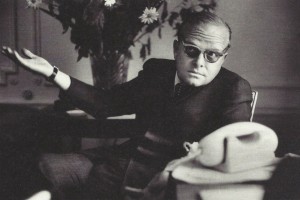

The Worthy Elephant: On Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood

For the fiftieth anniversary of the book’s publication, a discussion of craft, veracity and the literary appeal of true crime.

BY DAVID HAYES, SARAH WEINMAN HAZLITT BOOKS: JANUARY 27, 2016

-From In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

Has there been a more evocative opening of a nonfiction book than this first paragraph of Truman Capote’s “nonfiction novel,” In Cold Blood? This year is the 50th anniversary of the book’s publication in 1966 and it’s a reminder that with this book, Capote managed to simultaneously achieve commercial success and earn critical respect. But his modern nonfiction classic is also among the most controversial of all works of journalism.

In Cold Blood is seen as a pioneering book, and was originally published as a series in The New Yorker. It was the first conscious attempt to harness the techniques of fiction and journalism to document a crime, effectively inventing the modern true crime genre. Why a crime? Capote said “murder was a theme not likely to darken and yellow with time.” The book has sold millions of copies and is in print to this day; it has been translated into 30 languages and studied on university curriculums. It was the subject of a black-and-white movie in 1967, a colour remake in 1996, and films about the author’s reporting on the crime came out in 2005 (Capote, with Philip Seymour Hoffman as the titular character) and 2006 (Infamous, with Toby Jones).

At the heart of the text was the key technique that is perhaps the reason the work lends itself so well to cinema: reconstructing scenes and dialogue. Reading In Cold Blood is a singular experience, more engrossing than any of Capote’s fiction, showing a writer in command of his powers. But in the decades since the book was published, evidence of Capote’s elastic attitude toward the truth surfaced. In just one of many examples in Gerald Clarke’s 1988 biography of Capote, Clarke detailed how a key moment at the end of the book, when Kansas Bureau of Investigation Detective Alvin Dewey met a girlfriend of Nancy Clutter’s at her gravesite, never happened. In the 2012 book, Truman Capote and the Legacy of In Cold Blood, author Ralph L. Voss’ research emphasizes the ways that Capote changed timelines, invented scenes and exaggerated the role played by Detective Dewey, his hero, among many other examples of fact-fudging, many of them departing from Capote’s own 6,000 pages of notes.

It didn’t help matters that at the time Capote publicly declared his book was entirely factual. Also, he bragged that he didn’t use a tape recorder nor take many notes when conducting interviews, relying instead on what he claimed was a near-photographic memory. After Capote’s death in 1984, George Plimpton told The New York Times: “Sometimes he said he had ninety-six per cent total recall and sometimes he said he had ninety-four per cent total recall. He could recall everything but he could never remember what percentage recall he had.”

In a journal entry in 1967 about the actor Robert Blake, who portrayed Perry Smith in Richard Brook’s film adaptation of his book, Capote wrote: “Reflected reality is the essence of reality, the truer truth … all art is composed of selected detail, either imaginary or, as in In Cold Blood, a distillation of reality.”

In Cold Blood really should have carried the disclaimer “based on a true story,” like so many movies do today. But that wasn’t Capote’s ambition at the time. After successfully writing fiction, he wanted to create a masterpiece based on the power that comes when the public believes what they’re reading is true.

The book raises many questions. How much “fiction,” if any, is permissible in a work of creative nonfiction? Does artistic vision trump verifiable reportage? Can we forgive the sins of writers experimenting with long-form nonfiction at a time when clear guidelines hadn’t been established? Writer and crime specialist (both fiction and non) Sarah Weinman and I will discuss Capote and his legendary book… — David Hayes

CLICK ON THE LINK TO READ THE DISCUSSIOIN: In Cold Blood on Hazlitt