Down By the River

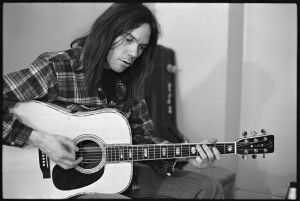

As a writer who loves music—and dabbled as a professional player as a teenager and in my twenties—I love reading (and writing) about music. Listening to this great Neil Young track today reminded me that twenty years ago, I wrote this short piece that was published in MOJO, the British music magazine.

____________

Da-da-da-da-da, da-da da-da da-da-da, da-da-da-da-da, da-da.

With that, Ne il Young kicked off one of rock’s defining guitar solos on one of rock’s definitive albums. He played the same note nineteen times, but he attacked it with such authority and passion that it sounded like he was playing a melody. That he then repeated the figure wasn’t just audacious; it felt revolutionary. The same note thirty-eight times! I thought at the time, even the legendary Charlie Parker had never done this.

il Young kicked off one of rock’s defining guitar solos on one of rock’s definitive albums. He played the same note nineteen times, but he attacked it with such authority and passion that it sounded like he was playing a melody. That he then repeated the figure wasn’t just audacious; it felt revolutionary. The same note thirty-eight times! I thought at the time, even the legendary Charlie Parker had never done this.

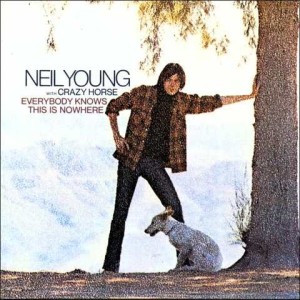

Down By the River, the fourth track on Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, is a nine-minute masterpiece. Released in 1969, on how many countless nights that year and for years to come did young people, their senses chemically heightened, lie with their heads between stereo speakers hypnotically drifting on Young’s edgy current? Over a bare-bones drumbeat, rolling bass line and Danny Whitten’s choppy guitar rhythm, Young’s brooding moan of a voice told an ageless tale of sadness, frustration and violence. (“Down by the river; I shot my lady…”) Like The Band’s Robbie Robertson, Young, a Canadian, understood the frontier legacy that animated the ragged margins of the American Dream.

For me and all my friends, and for many like us across North America, it was the stoner soundtrack of the day.

Following the frustrating internal conflicts with Buffalo Springfield (Young regularly feuded with band mate Stephen Stills) and a debut solo album soggy with studio effects and string sections, Young recorded Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere in just two weeks in his Topanga Canyon home studio. From the beginning it was clear he knew what he was after. He’d recruited some friends from a Los Angeles bar band called The Rockets, renamed them Crazy Horse, and said they were “the American Rolling Stones.” He brought to the sessions a new collection of songs that were unlike his past work. He’d scribbled Down By the River and the album’s other extended track, the moody Cowgirl in the Sand, on scraps of paper while lying in bed sweating out a 103 degree fever. With the exception of the upbeat Cinnamon Girl, all the material was similarly melancholic.

The album’s significance can’t be understated and the track around which the entire thing revolves is Down By the River. That song, and the sound of the whole album—jangly California folk-rock with a sawtooth edge—made it one of the early classics of underground FM radio and officially marked the beginning of Young’s remarkable solo legacy.