Where Ideas Come From

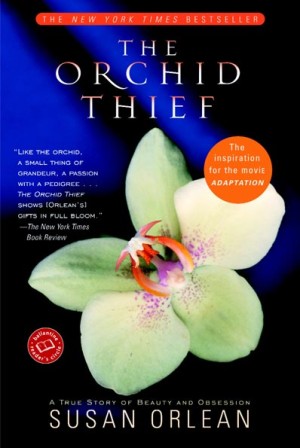

People who aren’t journalists, and journalism students, often ask, “where do feature ideas come from?” It’s one of the toughest parts of the business not because ideas aren’t out there by the thousands, but because recognizing them is a mix of technique, instinct, and experience. Sometimes they emerge from reading. Susan Orlean explained the genesis of her New Yorker feature on a maverick horticulturalist who stole orchids (“Orchid Fever”) which became her best-selling book, The Orchid Thief: A True Story of Beauty and Obsession.

I read lots of local newspapers and particularly the shortest articles in them, and most particularly any articles that are full of words in combinations that are arresting. In the case of the orchid story I was interested to see the words ‘swamp’ and ‘orchids’ and ‘Seminoles’ and ‘cloning’ and ‘criminal’ together in one short piece. Sometimes this kind of story turns out to be something more, some glimpse of life that expands like those Japanese paper balls you drop in water and then after a moment they bloom into flowers, and the flower is so marvelous that you can’t believe there was a time when all you saw in front of you was a paper ball and a glass of water.

Sometimes ideas emerge from talking to people. One day, while working on a story about affordable housing, I was seated at a community meeting beside a lawyer who worked at a pro bono legal organization. As we were leaving, she said, “you might want to talk to the executive director of my organization. Her husband is a lawyer representing three women who were brutally abused in a London, ON foster home in the ’60s and ’70s. They’re suing Children’s Aid and the London Police Services.” Who wouldn’t follow up on that? (It turned into a investigative feature for Chatelaine called: “The Sins of the Mother”. Other times I call a leading figure in an area and ask for suggestions for potential subjects. I’d heard about an upcoming international Rubik’s Cube championship at the Ontario Science Centre and The New York Times Magazine was interested. But how to find a character as the focus? I asked the organizer for the names of some people who were coming. He mentioned a 14-year-old boy from Boston, among the youngest to be signed up. My editor agreed with me that instead of one of the noted stars of the Rubik’s Cube world, it would be more interesting to follow this ordinary boy’s story, even if he didn’t make it to the finals. It became “Squaring Off”.

In Robert Boynton’s excellent book, The New New Journalism: Conversations with America’s Best Nonfiction Writers on Their Craft, Ted Conover talked about developing specific stories from the things that interest him. The elements that must be there, he said, are “the same as those required for good fiction: character, conflict, change through time and, if you’re really blessed, you get resolution.” He added that he was especially drawn to stories “that seem socially significant and under-reported, particularly if they allow me to participate in the story in some meaningful way. He also said:

In Robert Boynton’s excellent book, The New New Journalism: Conversations with America’s Best Nonfiction Writers on Their Craft, Ted Conover talked about developing specific stories from the things that interest him. The elements that must be there, he said, are “the same as those required for good fiction: character, conflict, change through time and, if you’re really blessed, you get resolution.” He added that he was especially drawn to stories “that seem socially significant and under-reported, particularly if they allow me to participate in the story in some meaningful way. He also said:

I might look for people involved in a conflict or a quest, some problem that does (or doesn’t) get resolved. Some stories come with a built-in thread. For example, I reported a story for The New York Times Magazine about AIDS orphans by focusing on a single mom with AIDS. [“The Hand-Off”]. She had a daughter but no other close relatives, and was looking for someone to adopt the daughter before she died. Can you imagine anything harder than that, seeking a replacement for yourself as a parent? Simply following her on this quest, and over all the bumps in the road, was the story’s thread.