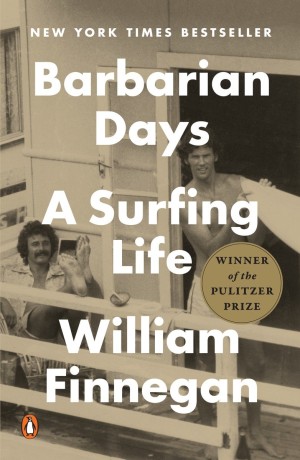

BOOKS THAT MATTER: “Barbarian Days”

For years I’ve been a fan of William Finnegan’s writing in The New Yorker. He’s been a staff writer since 1987, contributing remarkable pieces on geo-political conflicts and social dislocation in Europe, the Balkans, Africa, South & Central America, and the U.S. A multi-award winner, I’ve re-read several times “The Countertraffickers,” his story on Stella Otaru, an aid worker with the International Organization for Migration who reclaims victims of human trafficking. (It’s a model of narrative nonfiction, wonderfully reported, structured, and written.) He had, until two years ago, published four books: Crossing the Line (about the student anti-Apartheid movement in South Africa); Dateline Soweto (the difficult working lives of black journalists in South Africa); A Complicated War (upheaval caused by a devastating civil war in Mozambique); and Cold New World: Growing Up in a Harder Country (documenting the struggles of four working class teenagers in different parts of the U.S.). There had been hints of an interest in surfing (“Playing Doc’s Games,” Finnegan’s two-part article on a hard-core physician-surfer appeared in The New Yorker in 1992) and rumors that he was working on a memoir. But it still surprised many familiar with his distinguished, and serious, journalistic reputation when he produced Barbarian Days, a memoir obsessively focused on… surfing. And surprised many more when the book won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize in the Biography/Autobiography category.

I’ve never surfed and frankly have only the most modest curiosity about the sport. But a combination of my interest in Finnegan’s writing, the ecstatic reviews, and the Pulitzer put it on my reading list. Having just finished it, I’d say it’s nothing short of extraordinary.

Finnegan, who grew up in California and Hawaii, began surfing when he was a child and to call it an “obsession” is an understatement. It ruled his life and took him, as a young man, around the world seeking the most perfect waves. (The heart of the book is a four-year, coming-of-age trip he made with a friend in the late-’70s. Incredibly, that friend, Bryan Di Salvatore, also ended up writing for The New Yorker.) But unlike the stereotype of the sun-bleached, athletic, but simple-minded surfer dude, Finnegan was a voracious reader, aspiring writer, and thoughtful analyst of the world around him. He kept journals and, for the book, sought out letters he’d written to friends and family to help him reconstruct the past. I admit, I wondered how anyone — even a writer as talented as Finnegan — could sustain descriptions of riding waves over 450 pages. Yet he managed and his ability to capture what he call these “brief, sharp glimpses of eternity” are often breathtaking.

He describes his experience at Kirra, a suburb of the Gold Coast in Queensland, Australia, known when Finnegan was there as one of the premier surfing spots in the world. “The key to surfing Kirra was entering the wild section at full speed, surfing close to the face — pulling in — and then, if you got inside, staying calm in the barrel, having faith that it just might spit you out. It usually didn’t, but I had waves that teased me two, even three times, with the daylight hole speeding ahead, outrunning me, and then pausing and miraculously rewinding back toward me, the spilling lip seemingly twisting like the iris of a camera lens opening until I was almost out of the hole, and then reversing and doing it again, receding in beautiful hopelessness and returning in even more beautiful hope. These were the longest rides of my life.”

There were moments when I found myself wondering how the brilliant journalist I know today could have spent this much of his early life hunting for the perfect wave. The only explanation is that, like most obsessions, it’s as potent as the hardest drug. Finnegan may have best explained it in this passage which, like most of the book, is narrative nonfiction as its most lyrical and insightful: “Surfing always had this horizon, this fear line, that made it different from other things… Everything out there was disturbingly interlaced with everything else. Waves were the playing field. They were the goal. They were the object of your deepest desire and adoration. At the same time, they were your adversary, your nemesis, even your mortal enemy. The surf was your refuge, your happy hiding place, but it was also a hostile wilderness… The ocean was like an uncaring God, endlessly dangerous, power beyond measure.” He might have been talking about crack cocaine.

Still, I felt relieved when he admitted to what I had been thinking for many pages, that he and his buddy were “rich white Americans in dirt-poor places where many people, especially the young, yearned openly for the life, the comforts, the very opportunities that we, at least for the seemingly endless moment, had turned our backs on…” And after what began to seem a never-ending and insanely quixotic journey, enduring many brushes with death and a growing unease that he’s wasting his life, he finally wrote: “I felt unmoored from all possible explanations for this trip. It was certainly no longer a vacation…”

By the end of the book, Finnegan has a respected career as a journalist and a family but still surfs, although, as Leonard Cohen put it, he now “aches in the places where he used to play.” And he nearly dies in a moment of poor judgment that it’s hard to imagine him succumbing to on one of his foreign assignments. But after reading Barbarian Days, who could imagine him giving it up? Surfing was never a lark to Finnegan; it was the pursuit that philosophically defined his life.