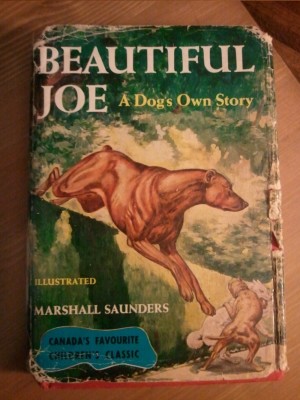

Beautiful Joe

Among the classic children’s books my parents read to me (and I later read myself), was Beautiful Joe. It was a fictionalized telling of a true story about a medium-sized mutt (probably part bull terrier and part fox terrier) owned by a farmer in Meaford, ON in the late 1900s who brutally abused him (chopping off his ears and tail). The dog would probably have died if he hadn’t been rescued by Walter Moore, a kindly local man who adopted him into his family.

In 1892, a Nova Scotian, Margaret Marshall Saunders, visited Meaford for her brother’s marriage to one of Walter Moore’s daughters. The story of the dog inspired and moved her. An aspiring writer as well as an animal activist, Saunders wrote a novel telling the story of the dog, while relocating the town from Ontario to Maine and changing Moore’s name to Morris. When she entered it in a literary contest sponsored by the American Humane Education Society, she made a decision not uncommon to Victorian-era women and used the more masculine-sounding Marshall Saunders. Like British author Anna Sewell’s Black Beauty, which had been published in 1877 and was already a children’s classic, Saunders used what was at that time still an uncommon narrative device — telling the story from the animal’s point-of-view.

I am an old dog now, and am writing, or rather getting a friend to write, the story of my life. I have seen my mistress laughing and crying over a little book that she says is a story of a horse’s life, and sometimes she puts the book down close to my nose to let me see the pictures.

I love my dear mistress; I can say no more than that; I love her better than any one else in the world; and I think it will please her if I write the story of a dog’s life. She loves dumb animals, and it always grieves her to see them treated cruelly.

I have heard her say that if all the boys and girls in the world were to rise up and say that there should be no more cruelty to animals, they could put a stop to it. Perhaps it will help a little if I tell a story. I am fond of boys and girls, and though I have seen many cruel men and women, I have seen few cruel children. I think the more stories there are written about dumb animals, the better it will be for us.

In telling my story, I think I had better begin at the first and come right on to the end. I was born in a stable on the outskirts of a small town in Maine called Fairport. The first thing I remember was lying close to my mother and being very snug and warm. The next thing I remember was being always hungry. I had a number of brothers and sisters–six in all–and my mother never had enough milk for us. She was always half starved herself, so she could not feed us properly.

I am very unwilling to say much about my early life. I have lived so long in a family where there is never a harsh word spoken, and where no one thinks of ill-treating anybody or anything; that it seems almost wrong even to think or speak of such a matter as hurting a poor dumb beast.

The man that owned my mother was a milkman. He kept one horse and three cows, and he had a shaky old cart that he used to put his milk cans in. I don’t think there can be a worse man in the world than that milkman. It makes me shudder now to think of him. His name was Jenkins, and I am glad to think that he is getting punished now for his cruelty to poor dumb animals and to human beings. If you think it is wrong that I am glad, you must remember that I am only a dog…”

Saunders won the contest and her book was published by the American Baptist Publication Society in 1894. It quickly became a phenomenon: the first Canadian book to sell more than a million copies and, today, it has sold 10-million and been translated into 10 languages. Following the success of Beautiful Joe, Saunders wrote more than 20 other books, many of them tackling issues of social justice such as the abolition of child labour, slum clearance, and the building of playgrounds for children. In her autobiography, she wrote: “I have had the honour of leading the old Ontario dog around the world on a chain of translations and rejoice in the report that he has become quite a propagandist for humanitarianism.”