Epistolary Nonfiction

I was thinking the other day about epistolary novels, based on documents, traditionally letters but sometimes diary entries or other correspondence (could be emails, tweets, texts, blog posts, etc). Over the years, I’ve read some I really liked — Samantha Harvey’s Dear Thief (a kind of “cover novel” of Leonard Cohen’s Famous Blue Raincoat); A. S. Byatt’s Possession; Alice Walker’s The Color Purple; and Nick Bantock’s Griffin and Sabine came to mind. (Perhaps Nicholson Baker’s Vox, told through phone sex conversations between the two protagonists, is a sub-genre.)

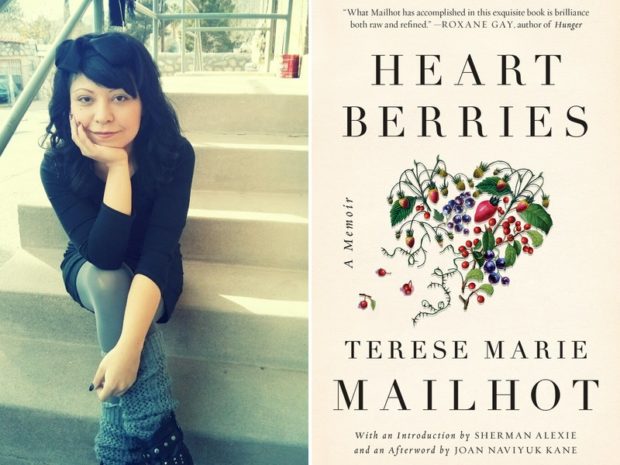

But what about epistolary nonfiction books? I don’t mean collections of notable people’s letters, but true nonfiction works. There are a few classic examples I can think of: James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time; Helene Hanff’s 84 Charing Cross Road; Rainier Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet; Marie Mailhot’s Heart Berries (written to her lover); Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me (written to his son); David Chariandy’s I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You (written to his daughter).

Why do it? There has to be a rationale. Writing a nonfiction memoir in tweets because that would be “modern” is not a good reason. The epistolary format can take readers deep into the head of the author but, typically, there isn’t much dialogue (few of us include dialogue in our letters, journal entries, emails, or tweets). Does an entire text message chain make sense or will readers lose interest? One challenge is that few of us have enough correspondence to build an entire nonfiction book around. Maybe looking at a fiction example where the author mixed narrative with the epistolary form would provide some clues to how it could work in nonfiction. My first thought was Jennifer Egan’s wonderful, Pulitzer-winning 2010 novel, A Visit From the Good Squad, which is a rollicking great read as well.

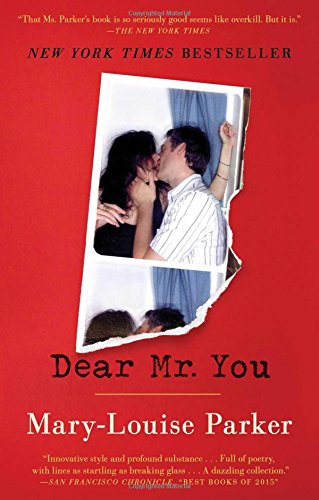

Or maybe really shake things up, as the actor Mary-Louise Parker did with her 2015 memoir, Dear Mr. You, written as a series of letters to men who mattered to her throughout her life. It’s non-fiction, and it’s inventive and flinty and funny, which isn’t a bad goal if you aim to please readers.