The Craft of Katherine Boo’s “Behind the Beautiful Forevers”

“Like most scavengers, Sunil knew how he appeared to the people who frequented the airport: shoeless, unclean, pathetic. By winter’s end, he had defended against this imagined contempt by developing a rangy, loose-hipped stride for exclusive use on Airport Road. It was the walk of a boy on his way to school, taking his time, eating air. His trash sack was empty on this first leg of his daily route, so it could be tucked under his arm or worn over his shoulders like a superhero cape. When Sister Paulette passed by in her chauffeured white van, it could be draped over his head. Sister Paulette-Toilet was how he thought of her now. He imagined her riding down Airport Road looking for children more promising than he.”

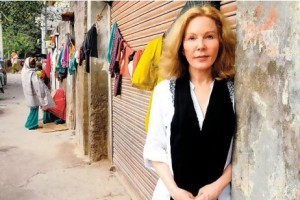

That’s one brief passage from the beautifully written and reported work of creative nonfiction, Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity, by the Pulitzer Prize winning New Yorker staff writer Katherine Boo. Told through several characters, it’s an account of the Mumbai slum, Annawadi, where 3,ooo people live on half an acre next to the city’s glittering new international airport and several luxury hotels, like a perfect juxtaposition of India’s extreme poverty and wealth.

Narrative nonfiction is not a quick-and-dirty craft; defining characteristics are “immersion research” and “saturation reporting.” Boo once spent seven years researching a book on a Washington housing project before abandoning it because she didn’t believe the story she wanted to tell — an authentic account of underclass in America — was working. Later, she found her inspiration among the migrant labourers and scrap-pickers of Annawadi, a slum so compact that it provided a natural frame for her story. (“Beautiful” and “Forever” are words included on ads for ceramic tiles that are painted on hoardings covering the concrete wall enclosing the slum.)

From 2007 to 2011, Boo, with the help of her translator, took notes as well as made audio and video recordings of many interviews and events. She’s explained that she usually wrote sections immediately after they happened, so much later wasn’t “agonizing, ‘Did this happen? What colour was her dress?’ The factual details are resolved and you have more freedom to go to the emotional heart.” On NPR’s Fresh Air, she explained how she approached her reporting: “I was just going where they went. I was doing what they did, whether it was teaching kindergarten or stealing scrap metal at the airport or sorting garbage. And I would sit and listen and talk to them intermittently as they did their work.”

Her eye is impressive. She describes how the children of Annawadi stand “close together, though there was plenty of space… for people who slept in close quarters, his foot in my mouth, my foot in hers, the feel of skin against skin had got to be a habit.” That kind of novelistic detail is the result of her commitment to methodical on-the-scene reporting. Many writers find it challenging, if not frightening, to immerse themselves so deeply, especially when the lives of their subjects are so different from their own. As Boo told The New York Times, “It’s O.K. to feel like an idiot going in as long as you don’t sound like an idiot coming out.”