The Secret of Structure Revealed, in Advanced Feature Writing at Ryerson University

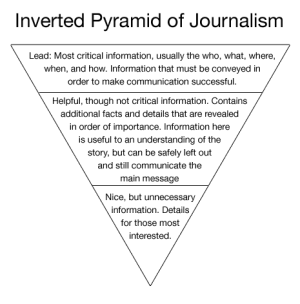

The most basic of news storytelling structures.

Anyone who’s been to journalism school or worked as a daily news reporter is familiar with the Inverted Pyramid. It’s a structural plan that reports the most important facts at the top of the story (the “lede” paragraph) and includes the rest of the information, in declining order of importance, in the following paras. It was a practical solution to a problem in the days when news reports were transmitted via telegraph. The Inverted Pyramid made sense because the most vital information was sent first; if there was a lost connection, an editor could still print the essential facts. Today, it’s still used, especially for fast-breaking, hard news events, when reporters are pressed for time, and in press releases. But it makes for lousy storytelling.

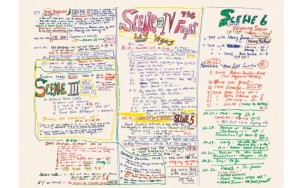

In my Advanced Feature Writing course, which is scheduled to run beginning on Thursday, September 15 (registration is open now: CDJN 118), we look at longform feature writing, which tells stories through dramatic narratives. This involves a more complex kind of structuring, especially for features running 2,000 words or longer. For example, have a look at a section of Gay Talese’s structural plan for his epic 15,000-word profile, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” published in Esquire in April, 1966. It covered a wall of his office in the basement of his Manhattan home and involved a rainbow of coloured pens.

Over a pair of three-hour classes in the middle of the semester I deconstruct, in para-by-para detail, the structure of four features illustrating four different, and common, kinds of stories. But contrary to what most people think, you don’t finish all your researching, reporting and interviewing and then, for the first time, consider a structural plan. Writers are thinking about structure long before they realize it. The moment, during your early reporting, when you think, oh, this scene I’ve just witnessed would make a perfect opening, you’re thinking structure. When you finish some background research and realize the material belongs about a third of the way into the feature, when readers will need to know this stuff, you’re thinking structure.

I know there’s a temptation, especially with ambitious young writers, to try a complicated structure, filled with flashbacks and flash-forwards and other structural devices. But the structure of a feature story is similar to the frame of a house: it’s an invisible support onto which you add the interesting stuff–the hip-roofed dormer, the key-stone at the top of an arched window, the fish scale wooden shingles–that people see. If anyone (other than an editor or fellow feature writer) notices the structure, it’s probably because they were confused. You want readers to notice your superb, original research, dramatic scenes and dialogue, perfectly timed anecdotes… not how the thing was put together.

Why is structure so tricky? Pulitzer Prize winning feature writer Tom French says, “One of the primary functions of stories is to find meaning out of the randomness around us. That’s why structure is so hard—it’s a way to create order out of something that’s not so orderly.”

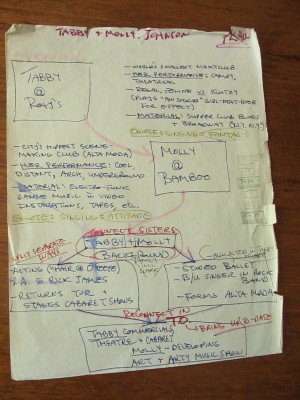

My structural plan for a profile of two sisters who were both singers in Toronto. (For Toronto Life)

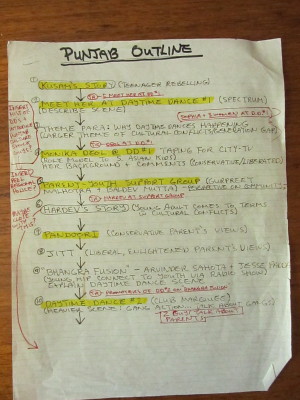

My structural plan for a story on a generation gap in Toronto’s South Asian community. (for Toronto Life)

(For more about the course, see the Teaching page on this web site)