Whose View to Choose?

I have long believed that all memoirs are written in first person. Why? Well, because the majority of them are, but also because readers expect the writer of a memoir to be a reliable narrator, someone they trust is telling the truth about themselves to the best of their memory.

Now, rather late in life, I’ve learned this isn’t always true. Laura Fraser’s An Italian Affair is written in second person, as is Paul Auster’s Winter Journey (“Some memories are so strange to you, so unlikely, so outside the realm of the plausible, that you find it difficult to reconcile them with the fact that you are the person who experienced the events you are remembering.”). In Another Bullshit Night in Suck City, Nick Flynn writes many of the chapters in the third person point-of-view of his father. Salman Rushdie’s memoir, Joseph Anton, written after the controversy surrounding his novel, The Satanic Verses, led to death threats, is written in third person. (Joseph Anton stands in for Rushdie.)

Point of view is the form of narration writers choose; it establishes who is telling the story. With first person, it’s as though the writer is sitting beside you, telling you her story, so it’s not surprising most memoir writers choose it. Second person creates the illusion that the reader is experiencing the events but it’s hard to sustain and can become annoying, especially over the length of a book. Third person is more authoritative, journalistic, but it distances readers from the personal story they’re hearing about.

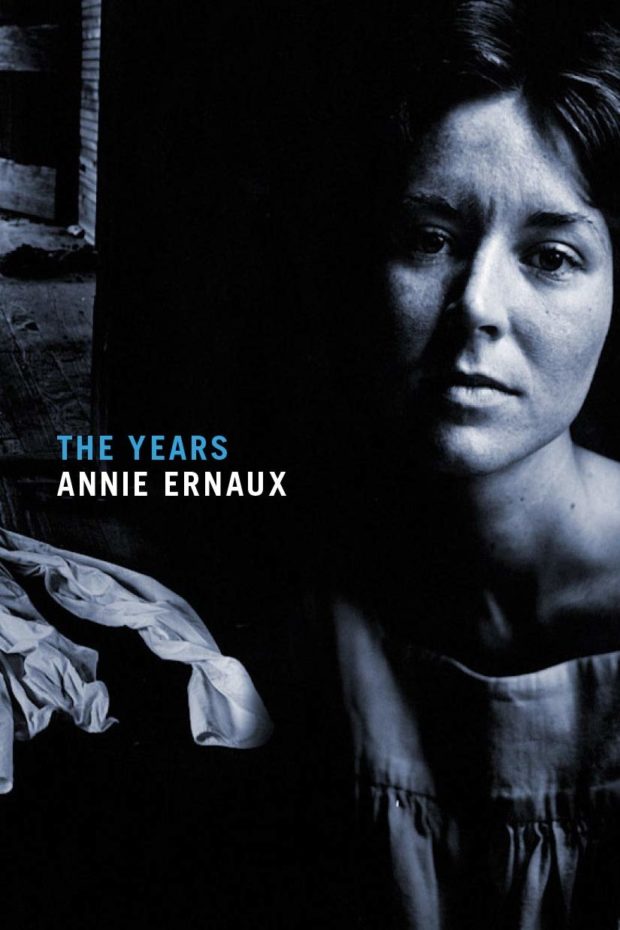

I had heard about the extraordinary French writer, Annie Ernaux, and her third person memoir, The Years. Curious, I read it and it succeeds at Ernaux’s stated goal, “I shall carry out an ethnological study of myself.”

It begins in 1940, when Ernaux was born, and ends in 2006. Sometimes she uses a collective “we,” as though Ernaux was referring to her entire generation. (“The thing most forbidden, the one we’d never believed possible, the contraceptive pill, became legal. We didn’t dare ask the doctor for a prescription…”) At other times, when she is referring to herself alone, she uses third person, as if she is a journalist observing herself. (“In this black-and-white photo, in the foreground, lie three girls and a boy, on their stomachs… She is the girl in the middle, the most ‘womanly.’ Her hair is combed George Sand style in flat bands on either side of a center part. her broad shoulders are bare, and her clenched fists emerge oddly from beneath her torso…”)

The point-of-view isn’t the only surprising thing about this memoir. To an unusual degree, it alternates between a kind of socio-literary history of France between the Second World War and the 21st century and a personal memoir. Describing the evolving consumerism that is consuming society, she writes, “Advertising provided models for how to live, behave, and furnish the home. It was society’s cultural monitor. Kids requested fruit-flavored Evian water (‘fortified’), Cadbury cookies, Nutella, a slot-load portable record player for listening to songs from the Aristocrats, remote-controlled cars, and Barbie dolls. Parents hoped that all the things they gave their kids would deter them from smoking hash when they were older…”

But, a paragraph later, Ernaux will bite into a madeleine and shift to the deeply personal, albeit omniscient third person, narration. After her marriage ends and her children are adults, she describes the younger lover she acquired. “She knows the main element of their relationship is not sexual, not as far as she’s concerned. Through the boy she can relive something she thought she would never experience again. When he takes her to eat at Jumbo, or greets her with The Doors and they make love on a mattress on the floor of his icy studio flat, she feels she is replaying scenes from her student life, reproducing moments that have already occurred…”

So, this experimental memoir is built around conventional memories of her life, a potted history of France in her lifetime, fragments of popular culture, and lists of things she and her generation have seen, or heard of, or misunderstood. For readers, it is a process of sifting through images and memories as much as it is an act of reading. Ernaux proves that it’s possible to write a memoir that is both personal and impersonal.