What is Creative Nonfiction?

A friend, who is not in the journalism or publishing fields, recently asked me “what is creative nonfiction?” Since I’m part of the faculty of the University of King’s College’s MFA in Creative Nonfiction, I should know. But it can be a tricky term to define.

The nonfiction part refers to telling true stories, not making them up. The creative part refers to using all of the techniques of writing — including those used by fiction writers — to make the stories compelling and dramatic. That means everything from scene-setting, dialogue, and character development to internal monologues. At its best, creative nonfiction holds the attention of readers, entertaining them while simultaneously providing the depth, context, and reflection necessary to understand complex issues and events and capture the complexity of individuals.

As Norman Sims points out in his introductory essay to the anthology, Literary Journalism: A New Collection of the Best American Nonfiction, the strength of this writing – a blend of sociology, anthropology, memoir writing, fictional techniques, history, and standard news reporting – is in the way writers become personally engaged with their subjects. Whether this is done explicitly – some writers involve themselves as characters in the unfolding events – or implicitly, via a strong point of view and the authoritative use of detail – the result is distinct from the detached, “objective” voice associated with traditional news stories, government and corporate reports, and textbooks.

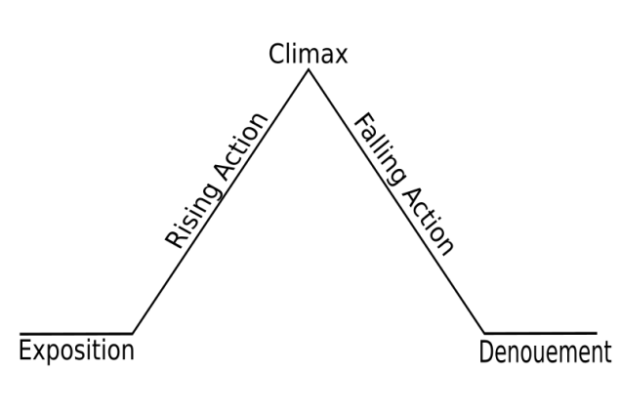

The traditional narrative arc (sometimes called a story arc) in fiction is usually described as exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and denouement. Creative nonfiction writers may use this, too.

Although not necessarily. There are other structural forms that can work, such as “braiding” (interweaving contrasting or complementary threads that may offer more than one perspective or toggle between present and past; for example, Lorri Neilsen Glenn’s Following the River: Traces of Red River Women ); “collage” (assembled from seemingly fragmentary bits and pieces but successful coalescing by the end; for example, Beth Ann Fennelly’s Heating and Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs); or parallel narrative (including two or more separate narratives linked by a common event, character, or theme; an example is John Hersey’s Hiroshima).

Whatever creative literary techniques or structural forms a writer uses, it isn’t creative nonfiction unless the story hews as closely as possible to researched and reported information. Unless the work is demonstrably nonfiction, not fiction.