Rereading A Depression Classic

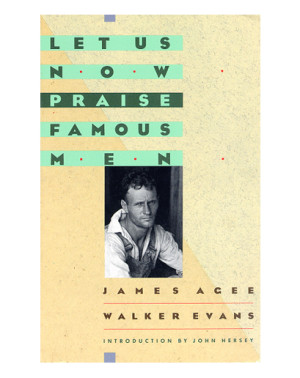

I recently reread Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the best known part of a book by novelist James Agee and photographer Walker Evans, published in 1941 under the title: Cotton Tenants: Three Families. It began as a magazine article—commissioned by Fortune in 1936—that went rogue. Agee and Evans were sent to document the lives of sharecropper families in the American South during President Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal” efforts to help those most victimized by the Great Depression. They spent eight weeks living among three families in rural Alabahama, Evans taking stark photos of men, women and children clinging to shreds of dignity and Agee scribbling detailed notes which he turned into a torrent of often disorienting, colon-clogged (Agee loved that punctuation) text that, to Fortune’s editors, must have seemed like passages from Joyce’s Ulysses rather than magazine journalism:

I recently reread Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the best known part of a book by novelist James Agee and photographer Walker Evans, published in 1941 under the title: Cotton Tenants: Three Families. It began as a magazine article—commissioned by Fortune in 1936—that went rogue. Agee and Evans were sent to document the lives of sharecropper families in the American South during President Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal” efforts to help those most victimized by the Great Depression. They spent eight weeks living among three families in rural Alabahama, Evans taking stark photos of men, women and children clinging to shreds of dignity and Agee scribbling detailed notes which he turned into a torrent of often disorienting, colon-clogged (Agee loved that punctuation) text that, to Fortune’s editors, must have seemed like passages from Joyce’s Ulysses rather than magazine journalism:

“The house and all that was in it had now descended deep beneath the gradual spiral it had sunk through; it lay formal under the order of entire silence. In the square pine room at the back the bodies of the man of thirty and of his wife and of their children lay on shallow mattresses on their iron beds and on the rigid floor, and they were sleeping, and the dog lay asleep in the hallway. Most human beings, most animals and birds who live in the sheltering ring of human influence, and a great portion of all the branched tribes of living in earth and air and water upon a half of the world, were stunned with sleep. That region of the earth on which we were at this time transient was some hours fallen beneath the fascination of the stone, steady shadow of the planet, and lay now listing toward the last depth; and now by a blockade of the sun were clearly disclosed those discharges of light which teach us what little we can learn of the stars and of the true nature of our surroundings…”

Maybe what came next isn’t surprising, considering Agee had described his ambition to produce a journalism-based “independent inquiry into certain normal predicaments of human divinity.” When Fortune rejected the manuscript, Agee wrote several hundred more pages of dense prose, later published by Houghton Mifflin. But the resulting book didn’t become popular, let alone acknowledged as a classic and studied as it is today, for many more years.

In the opening pages, Agee ruminated on the nature of journalism. It’s a critique that really isn’t far off the ideas of Noam Chomsky and other progressive media critics decades later:

“It seems to me curious, not to say obscene and thoroughly terrifying, that it could occur to an association of human beings drawn together through need and chance and for profit into a company, an organ of journalism, to pry intimately into the lives of an undefended and appallingly damaged group of human beings, an ignorant and helpless rural family, for the purpose of parading the nakedness, disadvantage and humiliation of these lives before another group of human beings, in the name of science, of ‘honest journalism’ (whatever that paradox may mean), of humanity, of social fearlessness, for money, and for a reputation for crusading and for unbias which, when skillfully enough qualified, is exchangeable at any bank for money…”