The Cold, Hard Facts About In Cold Blood

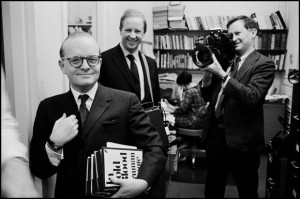

The occasion: This month marks the 50th anniversary of Truman Capote’s classic book, In Cold Blood, the story of the brutal murder of a farmer and his family in rural Kansas.

What he said: Capote called it a “nonfiction novel” and told George Plimpton in a 1966 Paris Review interview: “One doesn’t spend almost six years on a book, the point of which is factual accuracy, and then give way to minor distortions.”

What he did: In June 1966, Esquire published an article called “In Cold Fact.” The writer, Philip K. Tompkins, had talked to local residents and authorities who Capote had interviewed as well as studied trial records. Tomkins reported inaccuracies of various kinds, ranging from the final words spoken by one of the murderers, Perry Smith, to the way a horse belonging to one of the murdered children had been sold.  (Capote’s version of the sale provided greater symbolism.) In Gerald Clarke’s 1988 biography of Capote, the author reported on how a key moment at the end of the book, when Detective Dewey met a schoolmate of the murdered youngest child, Nancy Clutter, in a cemetery, never happened.) In the 2012 book Truman Capote and the Legacy of In Cold Blood, author Ralph L. Voss’ research emphasizes the ways that Capote changed timelines, invented scenes and exaggerated the role played by his hero, Kansas Bureau of Investigation Detective Alvin Dewey, among other examples of fact-fudging, many of them departing from Capote’s own notes.

(Capote’s version of the sale provided greater symbolism.) In Gerald Clarke’s 1988 biography of Capote, the author reported on how a key moment at the end of the book, when Detective Dewey met a schoolmate of the murdered youngest child, Nancy Clutter, in a cemetery, never happened.) In the 2012 book Truman Capote and the Legacy of In Cold Blood, author Ralph L. Voss’ research emphasizes the ways that Capote changed timelines, invented scenes and exaggerated the role played by his hero, Kansas Bureau of Investigation Detective Alvin Dewey, among other examples of fact-fudging, many of them departing from Capote’s own notes.

What to make of it all: In a journal entry in 1967, Capote wrote: “Reflected reality is the essence of reality, the truer truth … all art is composed of selected detail, either imaginary or, as in In Cold Blood, a distillation of reality.” Based on the evidence, though, In Cold Blood really should be presented as “based on a true story.” Still, he lived and worked in a different era, when contemporaries like Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion and Gay Talese were experimenting with the form. Even today, there’s little agreement on a quantifiable set of rules for long-form feature writing, so I’m inclined to “grandfather” this early work of creative nonfiction. Read it with an admiring, but skeptical, eye.