Voice and Memoir

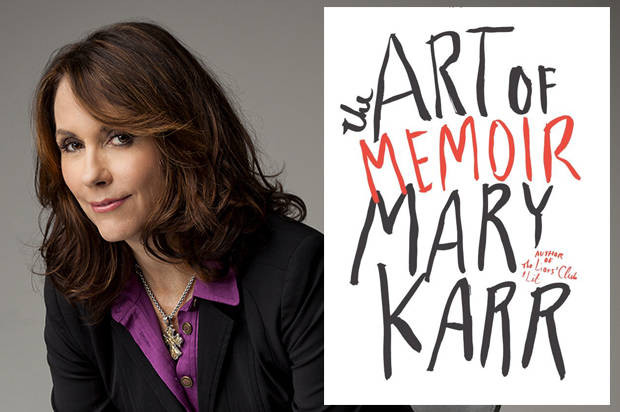

In Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir, she writes about “voice” being the key element in all writing. But, she continues, “each great memoir lives or dies based 100 percent on voice. It’s the delivery system for the author’s experience — the big bandwidth cable that carries in lustrous clarity every pixel of someone’s inner and outer experience. Each voice is cleverly fashioned to highlight a writer’s individual talent or way of viewing the world.” It’s not the events and facts of a writer’s experience, then, it’s whether you trust the writer’s telling of them.

Voice is evident from the moment you open Karr’s influential 1995 memoir, The Liar’s Club, often credited with kicking off a renaissance in memoir-writing. Growing up in hard-scrabble southeast Texas, Karr’s working class father is mostly likable but has elevated lying to a high art. Meanwhile, the silent force is her quiet, artistic, unhappy, abusive, alcoholic mother who descends into madness (but not before an epic scene involving her two daughters and a butcher knife). Early in the book, Karr writes, “It was never Mother who called us. Mother rarely even came out in the front yard since Mr. Sharp had told her she was going to hell for drinking beer and breast-feeding me on the porch. ‘You could see evil in the crotch of a tree, you old fart,’ she was supposed to have said in reply…”

The Liar’s Club is 150 proof Southern Gothic and Karr and her sister are products of that world. “After I grew up, the only man ever to punch me found himself awakened two nights later from a dead sleep by a solid right to the jaw, after which I informed him that, should he ever wish to sleep again, he shouldn’t hit me. My sister grew up with an almost insane physical bravery: once in the parking lot outside her insurance office, she brushed aside the .22 pistol of a gunman demanding her jewelry. ‘Fuck you,’ she said and opened her Mercedes while the guy ran off. The police investigator made a point of asking her what her husband did, and when she said she didn’t have one, the cop said, ‘I bet I know why.’ “

So there’s the voice: sometimes matter-of-fact in its sharply detailed observations; sometimes gritty, reflecting the chaotic nature of her upbringing and environment. One provides verisimilitude; the other emotional authenticity. Having discovered her voice, whatever Karr writes is engaging but she’s also been accused of representing the modern memoir’s weakness: too often a kind of selfie of the soul. A memoir has to be much more than transcribed therapy sessions. From The Art of Memoir:

“The secret to any voice grows from a writer’s finding a tractor beam of inner truth about psychological conflicts to shine the way. While an artist consciously constructs a voice, she chooses its elements because they’re natural expressions of character. So above all, a voice has to sound like the person wielding it — the super-most interesting version of that person ever — and grow from her core self.”

That’s also the biggest challenge. In real life, people overcome childhood trauma and fight their way past formidable obstacles by repressing or re-interpreting these experiences, making them into something that allows them to survive. The memoirist has to re-engage with difficult material to write truthfully about it, no matter how painful it may have been. Questioning memories that may have been reinvented is part of the deep research necessary to make a memoir work. But ultimately, readers won’t know what’s invented. They will accept or reject a memoir based almost solely on its voice.

“Pretty much all the great memoirists I’ve met,” writes Karr, “sound on the page like they do in person. If the page is a mask, you rip it off only to find that the writer’s features exactly mold to the mask’s form, with nary a gap between public and private self.”