Memoir as Psychological Thriller

Spoiler alert: If you haven’t read the book & don’t want the resolution revealed, avoid the final two paras.

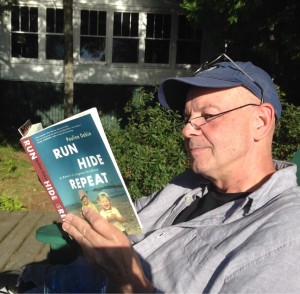

I met noted broadcaster and journalist Pauline Dakin when she enrolled in the University of King’s College’s MFA in Creative Nonfiction. She had two book ideas. One addressed the kind of medical and health issues she was known for through her CBC Radio work. The other was a memoir. What I remember understanding of it at the time was that it involved an alcoholic father, who didn’t live with the family, with ties to the Mafia and a childhood spent on the run.

Pauline’s childhood was in a constant state of upheaval, the family often moving at a moment’s notice. The children had to keep puzzling secrets and, as Pauline notes, quoting the Swiss physician and counselor Paul Tournier, “nothing makes us so lonely as our secrets.” Then, when she was in her early 20s, her mother told her that her father had been involved in organized crime and they’d been running from the Mafia, with the help of a government-sanctioned anti-organized crime unit that was almost entirely below-the-radar, so secret even Members of Parliament didn’t know about it. Their connetion to it was a charismatic United Church minister, Rev. Stan Sears, who had become Pauline’s mother’s lover and sometimes played the role of a benevolent father figure to Pauline.

These events were confusing and bewildering to Pauline for years until she began approaching her own story like the top journalist she had become. Her skepticism and relentless probing into the Byzantine twists and turns of Sears’ narrative eventually exposes it for what it was: a delusional man’s fantasy world.

But that’s just the plot. The story also encompasses Pauline’s generosity toward her always loving mother, who had fallen under Sears’ spell, and even empathy for Sears, about whom she develops a theory that might explain his behavior. Not that any explanation could change the havoc the man had brought into one family’s life.