Working Class Martyr

On December 8, 1980, I was working on a deadline for one article or another on my Underwood typewriter when my phone rang. It was my friend, singer Marian Tobin, calling from the El Mocambo where she and her two singing partners who made up The Honolulu Heartbreakers were performing that night with Professor Piano and the Canadian Aces. A friend, Colin Linden, had just walked in the bar to announce that John Lennon had been murdered.

On December 8, 1980, I was working on a deadline for one article or another on my Underwood typewriter when my phone rang. It was my friend, singer Marian Tobin, calling from the El Mocambo where she and her two singing partners who made up The Honolulu Heartbreakers were performing that night with Professor Piano and the Canadian Aces. A friend, Colin Linden, had just walked in the bar to announce that John Lennon had been murdered.

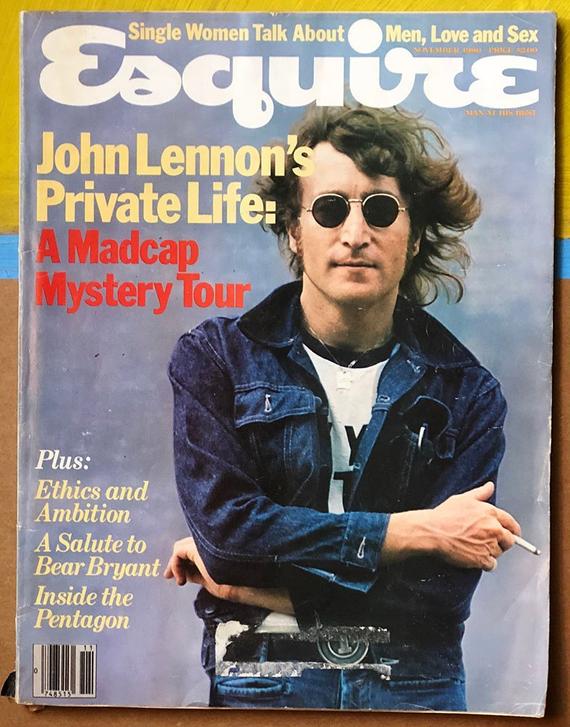

I was stunned, of course, but maybe even more so because lying on the floor beside my bed was the December issue of Esquire magazine. I had just read the cover story, about John Lennon, the day before. The writer, Laurence Shames, had spun a tale about how Lennon, in semi-retirement, wouldn’t cooperate with the writer so Shames had written one of those “how-I-didn’t-get-the-story-but-managed-to-produce-this” articles that we journalists often pull off rather than abandon a story and sacrifice our fee. It became a rather devil-may-care accounting of all of Lennon’s mansions (at least, four of them; there were more), cows (some of the couple of hundred on properties Lennon owned), a section of private beach in Florida, a greenhouse in upstate New York, a failed attempt to find his yacht, microfilms of deeds and mortgages worth millions… “And the more I found,” Shames wrote, “the happier I was that I hadn’t succeeded in smoking out Lennon himself. He wouldn’t have been the Lennon I went looking for.”

The Lennon Shames was looking for was the conscience of the ’60s, the working-class hero, the truth-seeker, the guy who sometimes put his foot in his mouth (“we’re more popular than Jesus now,” which sounded much less offensive when read in context of his other remarks at that press conference). Was the fact that Lennon now resided quietly in a luxury residence in Manhattan, a rich celebrity, a symbol of the death of the optimism and activism of the ’60s? That’s more or less the article Shames wrote and Esquire published (and to be fair, despite the disappointment Shames clearly felt, he wrote sympathetically and rather reverently about Lennon).

To be honest, we wouldn’t be talking about that long-ago article today except for one snag, a danger that in the journalism business is called “lead time.” That is, the weeks between finishing all work on an article and it’s sent to the printer, and the time it takes to appear on newsstands and in the homes of subscribers. Getting caught out on lead time is a terror residing in the back of the minds of every editor and writer. In this case, the December issue of Esquire was only out about ten days or so before Lennon was murdered.

Even that story has mythic elements. Earlier in the evening, Mark David Chapman had approached Lennon, walking with Yoko Ono, outside The Dakota, where they lived. Chapman, who must have appeared to be just any fan, asked Lennon to sign his copy of of the just-released new album, Double Fantasy. Lennon and Ono then went to the Record Plant Studio for a recording session. Later, as the couple returned to The Dakota, the obsessed and disturbed Chapman fired five hollow-point bullets from a .38 special revolver, four of which hit Lennon in the back. Rather than running away, Chapman remained at the scene reading Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye until he was arrested by police officers.

Of course, Lennon became an instant martyr in the eyes of the world, especially the members of the Baby Boom generation who had revered him. Although he didn’t talk to Lawrence Shames and Esquire, he had participated in a long interview for Playboy which was published a month after his death, in January, 1981. In it, he said more or less what he might have said to Shames. At one point, he told interviewer David Scheff, “You’re like the typical sort of love-hate fan who says, ‘Thank you for everything you did for us in the ’60s—would you just give me another shot? Just one more miracle?’”