The Book That Changed My Life

As a teenager and into my early 20s, I loved writing and music. Influenced by the rock revolution led by The Beatles and Stones, I played bass in a band. Influenced by Rolling Stone magazine, Creem, and The Village Voice‘s pop music coverage, I planned to attend journalism school. Instead, in 1975, I became an undergrad at York University’s Glendon College. I thought I’d get an honour’s English degree as a way of launching a journalism career. The writer-in-residence there was Michael Ondaatje.

I asked his secretary whether I could sit in on one of his graduating year seminars. After asking Ondaatje, she said, yes, so long as you sit quietly at the back. When I did two things struck me.

- For someone who had been touring with a band in rough-and-tumble norther Ontario bars, the graduating year students seemed like they’d never left their parent’s basements. It no longer struck me as so attractive a route into journalism.

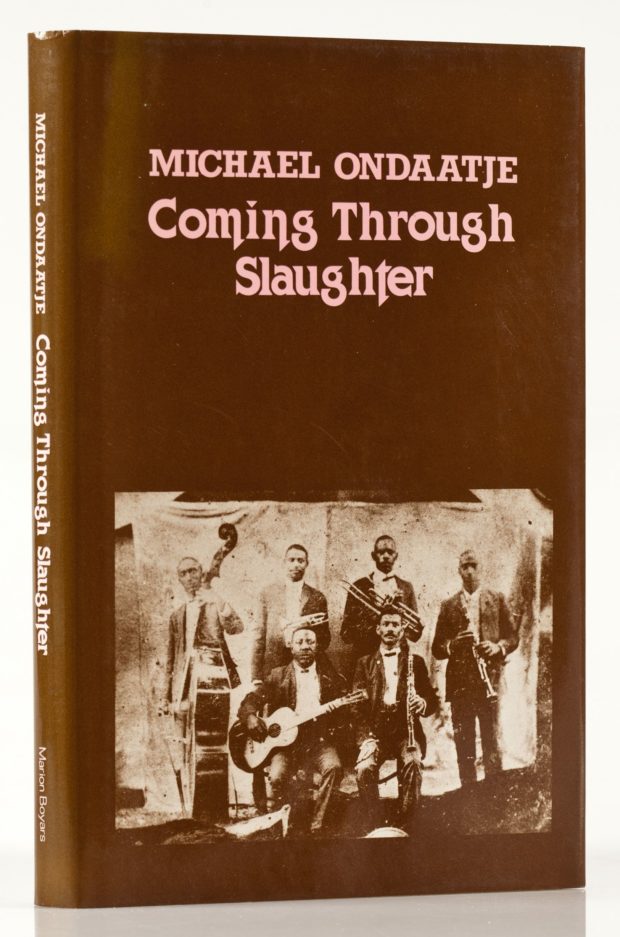

- Ondaatje talked at length about a project he was working on, a novel of sorts, based on a great deal of research he’d conducted into Buddy Bolden, an African-American cornetist in the early 1900s considered one of the forefathers of jazz. Died so young there weren’t even field recordings of his playing, just oral accounts from the likes of Louis Armstrong who remembered hearing him. This was creative writing, based on nonfiction, about music. I was sold.

When Coming Through Slaughter was published a year later, in 1976, I devoured it and have read it many times since then. Every two or three years, on average. It’s a haunting, atmospheric story that beautifully captures a brilliant, doomed musician as well as the place, the Storyville district of New Orleans. It convinced me to go to journalism school and launch the career that has sustained me for nearly four decades.

Loosely chronological, it’s divided into three acts, covering the year 1907. The first sketches Bolden’s life in New Orleans, with his wife, Nora. The second follows his disappearance and ill-fated affair with the seductive Robin. The third finds him back in New Orleans, sinking deeper into the mental illness that will incapacitate him. Twice during this time he passes through a town named Slaughter, signaling his exodus and return.

Scene after scene of prose-poetry leaves me breathless. Like this fight between Bolden and a family friend, Tom Pickett, with whom his wife is involved.

He picks up a large piece of mirror and skims it hard across the room at me. It hits the wall to the left of my shoulder but it came really fast and it scares me. I know he will slice me. He takes the next piece and jerks it at me twenty feet away and it comes straight for me. My neck. Is coming for me I’m dead I can’t. Move. And then catches on a muscle of air and tilts up crashing above my head. Door opens near me. Nora. What! Stay back…

And later, as he reaches the end of sanity, Bolden hallucinates during a brass band march along Iberville Street. A flamboyantly dancing woman is like Nora and Robin combined, the purest eroticism.

March is slowing to a stop and as it floats down slow to a thump I take off and wail long notes jerking the squawk into the end of them to form a new beat, have to trust them all as I close my eyes, know the others are silent, throw the notes off the walls of people, the iron lines, so pure and sure bringing the howl down to the floor and letting in the light and the girl is alone now mirroring my throat in her lonely tired dance…

And then the end.

…take on the last long squawk and letting it cough and climb to spear her all those watching like a javelin through the brain and down into the stomach, feel the blood that is real move up bringing fresh energy in its suitcase, it comes up flooding past my heart in a mad parade, it is coming through my teeth, it is into the cornet, god can’t stop god can’t stop it can’t stop the air the red force coming up can’t remove it from my mouth, no intake gasp, so deep blooming it up god I can’t choke it the music still pouring in a roughness I’ve never hit, watch it listen it listen it, can’t see I CAN’T SEE. Air floating through the blood to the girl red hitting the blind spot I can feel others turning, the silence of the crowd, can’t see

Bolden’s stroke didn’t kill him, but he spent the rest of his tormented life in an asylum in nearby Jackson until his death in 1931.

The book is fragmented, constructed around a series of vignettes including interviews, lists of songs, and medical reports. Sometimes, as Ondaatje uses techniques of oral history, biography, and nonfiction reconstruction, I forget it’s a novel. It’s fiction spun from fact, resembling, in a more experimental way, another favorite novel, E. L. Doctorow’s Ragtime. It’s reads like an improvised jazz tune, performed with words instead of sound.