Who Wrote the Best Ghostwritten Book?

These days, I make my living as a teacher and a ghostwriter of books. Ghostwriting is a mysterious occupation. Since discretion is one of its chief virtues, I can rarely name my clients. And one of the most important roles of a ghostwriter is to express the words of another person as they would have if they could write their own book. So, if a client’s book would, logically, read like that of an economist with an ability to express herself in clear language, that’s how it should read. The ghostwriter’s talent is mostly like that of actors, who take on the personalities of the characters they have been hired to play.

I’m sometimes asked, what is the greatest ghostwritten book you have read? That’s easy. Andre Agassi’s 2009 autobiography, Open. It was ghostwritten by the U.S. journalist and novelist, J. R. Moehringer (who also ghostwrote Nike founder Phil Knight’s autobiography, Shoe Dog). I don’t play tennis nor follow it so the book was off my radar. My writer-friend, David Macfarlane, who is a tennis buff, told me about it and it lived up to his rave.

Moehringer had written a memoir called The Tender Bar (2005), which Agassi had read and decided this was the person to help him with his own book. It’s unusual for a sports memoir for a number of reasons, not the least of them the lack of cliches. (I don’t recall the phrase “pursuing his dream” being used even once.) In fact, the book is more about how Agassi hated tennis ever since he was a child, how it was a prison that he consistently wanted to escape, even as he rose in stature, and about the abusive relationship he had with his father, who brutally molded his son into a champion. As his career rises, Agassi openly admits, without apology, to myriad examples of bad behavior and drug abuse. This is a ghostwriter’s dream: a celebrity athlete willing to unapologetically and thoroughly explore his weaknesses and demons.

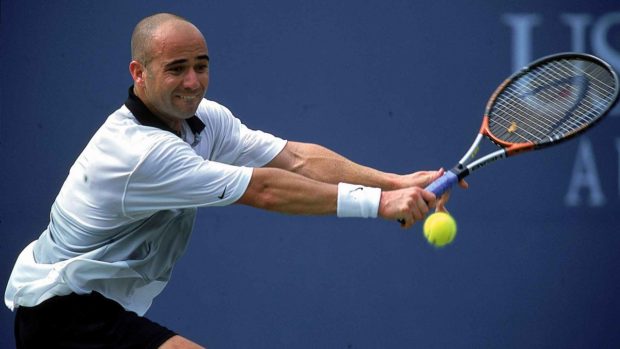

Agassi was loved and hated, like many sports stars. In the ’90s he sported a bizarre Rod Stewart-ish spiky, duo-toned mullet-ish ‘do, a look that led novelist and tennis lover David Foster Wallace to refer to him as “about as cute as a Port Authority whore.” (As it turns out, he was going bald and wearing a hairpiece.) He threw tantrums but was the dominant male player during his run. His two marriages — to Brooke Shields and, later, tennis star Steffi Graf, who also hated tennis — are deconstructed but not in salacious tabloid detail.

I could quibble about Open in one way. The occasional stream-of-consciousness passages and Agassi’s insights into himself sometimes read a bit too literary. (Agassi could have written this? Only if he’d had one hell of a literary gene.) But mostly I sensed that out of the reams of interviews the writer collected, the voluble Agassi spilled everything and Moehringer shaped it into something great.