Still Pictures: Memory, Memoir, & Photography

Janet Malcolm’s writing, in The New Yorker and elsewhere, has always been characterized by her ability to expose the self-delusions of others, reveal the true selves behind carefully-constructed personas. In Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory, she turns her briery eye on herself, producing what could almost be called an anti-memoir. A serious journalist, she clearly states her view of autobiography and memoir: “Memory is not a journalist’s tool. Memory glimmers and hints, but shows nothing sharply or clearly.”

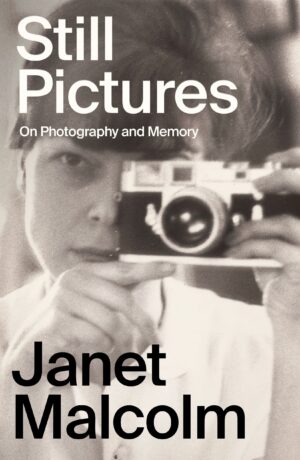

So, Malcolm, who died of lung cancer in 2021 without finishing the final chapter, makes a point of admitting that her own memories are often missing, incomplete, or inaccurate. She draws on photographs — the book is built around a dozen images, mostly fuzzy and black-and-white — as well as diary entries, letters, and other sources to support what she would no doubt describe as an inherently unstable structure. How often do memoirists admit, as Malcolm does at one point, “Who was I? Why did I act like that? What was going on in the room that I didn’t quite understand?”

The book begins with her Jewish parents fleeing Europe on one of the last civilian ships leaving Europe before World War II began, their savings depleted by payoffs to middlemen. They left behind a wonderfully rich cultural life for what would become a rather dull, middle-class one in the United States. (It could be worse; many refugees failed to rise above poverty). The rest of the book is made up of short vignettes. What it lacks in volume, though, it makes up for in sharp insights into how we construct and understand our pasts. “Memory does not narrate or render character,” she writes. “Memory has no regard for the reader.”

While Still Pictures doesn’t reach the heights of her great works of creative nonfiction — The Journalist and the Murderer; The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes; and In the Freud Archives — it is still a chance to experience among the sharpest, most acute writers this side of Joan Didion. And to challenge our ideas about what we think we know about our own histories. “The past is a country that issues no visas,” she writes. “We can only enter it illegally.”