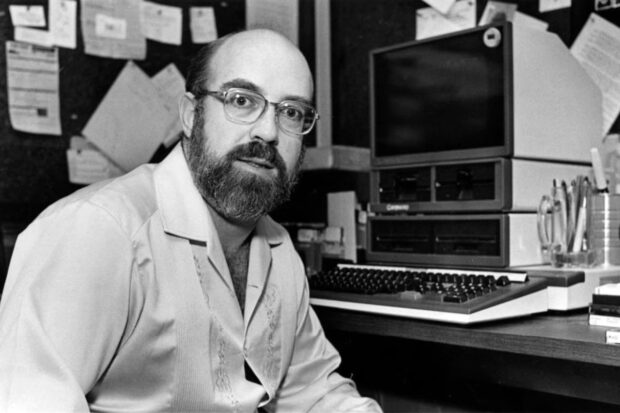

R.I.P. Jon Franklin

The late Jon Franklin was one of the founders, teachers, & great practitioners of literary journalism (also known as creative nonfiction, narrative nonfiction, or longform). He won the first Pulitzer Prize for feature writing in 1979 for a story called “Mrs. Kelly’s Monster,” which is a blow-by-blow of the day Dr. Thomas Ducker, a brain surgeon, operated on Edna Kelly, a woman with a deadly aneurysm. In cool, unsentimental prose, Jon builds suspense with the popping sound of the heart monitor, the imagery (when we finally see the aneurysm it’s the colour of rich, clotted cream), and the intense concentration of Ducker and his team as they probe their way, millimeter by millimeter, through the woman’s brain. It’s a master class in the art of feature writing, all the more so because (spoiler alert) the patient doesn’t survive. In the end, the hero, Ducker, must accept defeat and return to try to save another life and another after that.

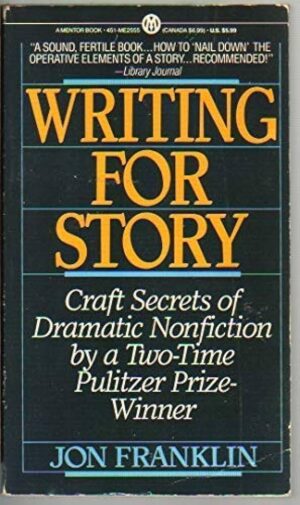

The story is featured in Jon’s most influential book, Writing For Story: Craft Secrets of Dramatic Nonfiction By a Two-Time Pulitzer Prize Winner, published in 1986. That was two years before I began teaching feature writing and it became a cornerstone of my courses. (It’s still in print today, nearly 40 years later.) In it, he explains how to apply the storytelling techniques of fiction to nonfiction. The short answer: use every technique of the novelist except making things up. I remember finding his phone number and calling him to ask him how he did the reporting for “Mrs. Kelly’s Monster.” He graciously spent two hours or more taking me through almost every sentence in that story explaining where he was in the operating room and how he found out about each detail. (Thus began a long-distance friendship that lasted for decades.)

The story is featured in Jon’s most influential book, Writing For Story: Craft Secrets of Dramatic Nonfiction By a Two-Time Pulitzer Prize Winner, published in 1986. That was two years before I began teaching feature writing and it became a cornerstone of my courses. (It’s still in print today, nearly 40 years later.) In it, he explains how to apply the storytelling techniques of fiction to nonfiction. The short answer: use every technique of the novelist except making things up. I remember finding his phone number and calling him to ask him how he did the reporting for “Mrs. Kelly’s Monster.” He graciously spent two hours or more taking me through almost every sentence in that story explaining where he was in the operating room and how he found out about each detail. (Thus began a long-distance friendship that lasted for decades.)

He used the same storytelling techniques to win his second Pulitzer, for explanatory journalism, in 1985 for “The Mind Fixers,” a seven-part series published in The Baltimore Evening Sun on how the emerging science of molecular psychiatry could become an alternative to the imprecision of psychoanalysis.

In 1994, Jon launched an early Internet experiment, a listserv called WriterL (for literary journalism). With his wife, Lynn Franklin (a mystery writer and editor) moderating, Jon led what became a high-spirited and far-ranging discussion of nonfiction writing in all its forms. It soon became the focal point for those who practiced and taught literary journalism in North America and abroad. With several hundred members involved, I remember participating in lengthy debates around interviewing practices, reconstructing scenes that the journalist didn’t witness, including a subject’s thoughts in addition to quotations, and whether Truman Capote’s 1966 book, In Cold Blood, which contained some egregious distortions of the truth, should be “grandfathered” because the form was relatively new at that time. (Part of that debate included the fact that what can be called the modern notion of literary journalism had been practiced, in a limited way, since shortly after the turn of the 20th century.) WriterL had a good run, but there was more and more competition for our online attention as the years passed and Jon and Lynn finally closed it in 2013.

At one point, Jon and Lynn were making an effort to monetize articles relating to WriterL. With input from Jon, I adapted a chapter of a media-related book of mine, which we called “A Reporter’s Story, ” and it became, for a time, the highest-selling WriterL article. When I got my first royalty cheque, I told Jon that I could, just barely, take him and Lynn out to McDonald’s.

In 2022, Jon and Lynn, assisted by the noted editor and writing coach, Stuart Warner, created an anthology of WriterL discussions. In the introduction to A Place Called WriterL: Where the Conversation was always about Literary Journalism, Warner accurately describes it as “robust conversations about the art of nonfiction writing that may have taken place 15 or 20 years ago but are still relevant and enlightening to writers today.”

Jon taught at the University of Maryland, Oregon State University, and then ran the journalism school at the University of Oregon. In 2002 he accepted a position back at the University of Maryland as the Merrill Chair of Journalism. Over the years, I often sought his counsel on teaching the craft. He always had suggestions for how to better teach the complexities of structure or help break a talented student’s writer’s block.

Sadly, Jon developed esophageal cancer two years ago, as he entered his 80s, and finally died in a hospice on January 21st. It saddened me that I’d lost a mentor and friend but I’m also reminded of something Jon wrote in the preface of Writing For Story that, when I read it in my early 30s, resonated, as it resonates today, to know that Jon lived his life this way. “For me as for most of my colleagues, craftsmanship began as a means to an end. It was the vehicle with which I would express my feelings and make for myself a place in the world. But in the process of paying my dues, of working and learning, it metamorphosed into something else, into a compulsion, into an addiction, into a love. And it has rewarded me beyond my wildest hopes.”