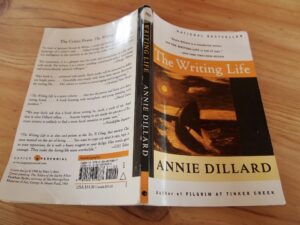

The Writing Life

I recently re-read Annie Dillard’s 1989 book, The Writing Life, and found it to be as companionable as I remembered from when I first read it three decades ago. In fact I can appreciate even more her musings on the pain, as well the pleasures, of writing.

The most famous quote from The Writing Life is this one: “When you write, you lay out a line of words. The line of words is a miner’s pick, a woodcarver’s gouge, a surgeon’s probe. You wield it, and it digs a path you follow. Soon you find yourself deep in new territory. Is it a dead end, or have you located the real subject? You will know tomorrow, or this time next year.”

Hmm, well that’s a relief of some kind.

Dillard is the author of many books, including Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1975, Teaching a Stone to Talk, and my personal favorite, An American Childhood. She also writes essays, poetry, literary criticism, and fiction. Is The Writing Life perfect? Not really. Like so many who write books about writing, there is sometimes a whiff of pomposity which reminded me a few times of those self-styled mystics promising to turn around your life. I’m probably too practical, or stodgy, to embrace this interpretation of the writing life.

Dillard is the author of many books, including Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1975, Teaching a Stone to Talk, and my personal favorite, An American Childhood. She also writes essays, poetry, literary criticism, and fiction. Is The Writing Life perfect? Not really. Like so many who write books about writing, there is sometimes a whiff of pomposity which reminded me a few times of those self-styled mystics promising to turn around your life. I’m probably too practical, or stodgy, to embrace this interpretation of the writing life.

But, to be fair, the book is less a self-help guide for aspiring writers and more of a variation on what characterizes most of her writing: meditations on nature and life. Often, what most stands out are the beautiful passages of descriptive writing. Like this one:

“The cabin was a single small room near the water. Its walls were shrunken planks, not insulated; in January, February, and March, it was cold. There were two small metal beds in the room, two cupboards, some shelves over a little counter, a wood stove, and a table under a window, where I wrote. The window looked out on a bit of sandflat overgrown with thick, varicolored mosses; there were a few small firs where the sandflat met the cobble beach; and there was the water: Puget Sound, and all the sky over it and all the other wild islands in the distance under the sky. It was very grand. But you get used to it. I don’t much care where I work. I don’t notice things. The door used to blow open and startle me witless. I did, however, notice the cold.”

Oddly, Dillard herself apparently doesn’t like the book. Her husband, Robert Richardson, wrote a biographical summary of his wife’s career which appears on the Annie Dillard web site. It includes the line: “In 1989 she published The Writing Life, a book she repudiates except for the last chapter, the true story of stunt pilot Dave Rahm.” No explanation is given for why she considers it such a failure.

No matter. The Writing Life was as good, or better, than I remembered it. And some of her thoughts about the writing process are both poetic and true.

“One of the things I know about writing is this: spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time. Do not hoard what seems good for a later place in the book or for another book; give it, give it all, give it now. The impulse to save something good for a better place later is the signal to spend it now. Something more will arise for later, something better. These things fill from behind, from beneath, like well water.”