Exploring a Grandmother’s Secret Life

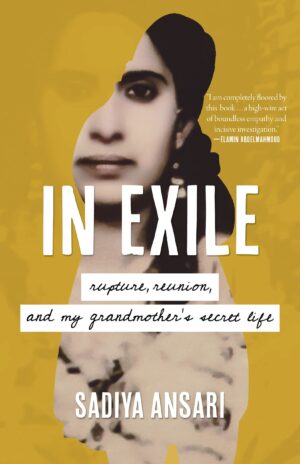

As we reach the end of 2024, I’d say my favourite book of the past year is Sadiya Ansari‘s In Exile: Rupture, Reunion, and my Grandmother’s Secret Life. Ansari is a Parkistani-Canadian journalist living in London, UK. She set out to investigate a family mystery, one that her parents and other family members had been disinclined to air: why her grandmother (Daadi) abandoned her seven children to follow a man from her ancestral home in Karachi to a village in the Punjab. (Then left him years later and gradually began re-entering her adult childrens’ lives.) By the time Ansari began investigating this family history, her Daadi, who had been living for years in her family’s home in Toronto, had died.

Ansari explores the history and cultural realities underpinning her Daadi’s life and how she chose to challenge cultural norms. This includes the pervasiveness of child marriages (her Daadi had been married at 14), how Pakistan’s Partition forced many families to become refugees, and how the modernization of the country resulted in new freedoms that mostly didn’t extend to women and their traditional roles.

Trying to piece together memories from family members both in Canada and abroad proved challening, as anyone familiar with memoirs knows. Ansari quotes the host of the podcast, Every Little Thing, as he distills the ideas of psychologist and neuroscientist Charan Ranganath, an authority on memory: “Remembering something isn’t like playing back a movie; it’s more like pulling in scraps from different parts of the brain.” There is another factor, too, of course. In an interview with Sheima Benembarek in Broadview magazine, Ansari said: “[Parents] want to give you a version of the story that suits them, for a variety of reasons. Whether that’s not wanting to answer more questions from their children, or upholding family mythology, consciously or unconsciously.”

At the end of the book, Ansari provides a most revealing essay about interviewing, families, and trauma. It challenges many journalistic norms — they don’t always work, nor are they always fair, when working on a memoir. As she writes, “Sometimes storytellers are given too much credit; sometimes we are just story takers. I didn’t want to just regurgitate my family’s history for the sake of good content. I wanted to try and recast Daadi from villain into human. But, of course, her children had already been grappled with this for decades.“